ÍNDICO Encounters with Edna Jaime and Mia Couto

In each other’s shoes

In the 1990s, before the lullaby on public television, on the flat of a building on 24 de Julho, in the city of Maputo, Edna Jaime (b. 1986), the daughter of a Ndau military man and a Chope mother, stared wide-eyed at the announcements of performances by the National Song and Dance Company.

“In art, you have to walk from discomfort to discomfort: the moment you feel comfortable, art dies,” Mia says.

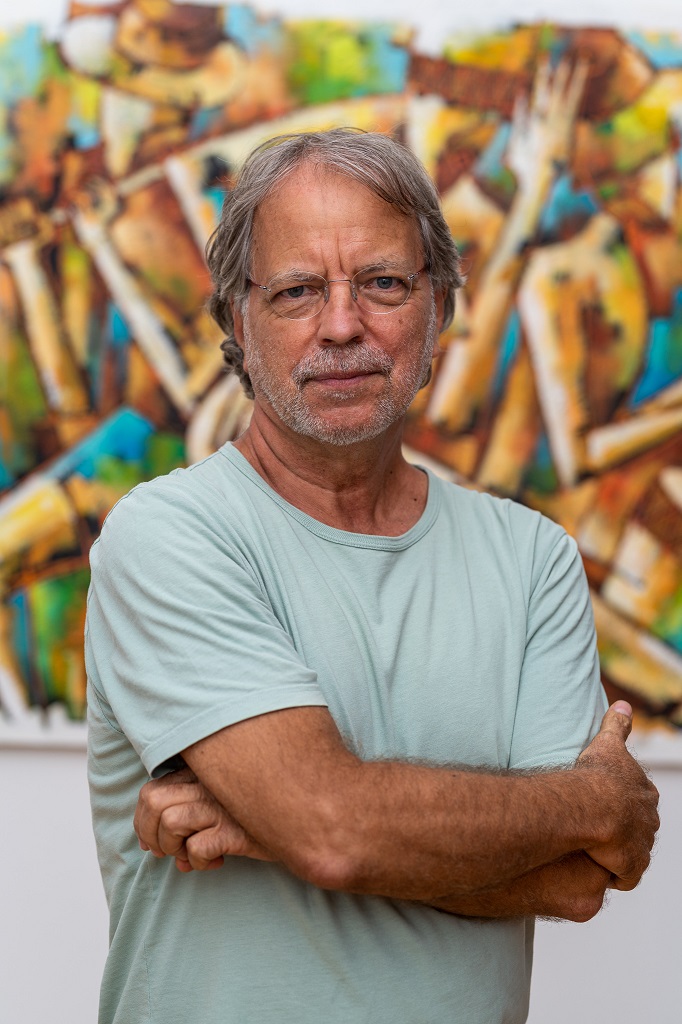

In the city of Beira, surrounded by books by his father, who was a writer, journalist and literary editor, the writer Mia Couto (b. 1955), a shy child, fell in love with words, with imagination.

The two are now seated for a conversation.

Edna Jaime uncovers her past and the light of memory reveals an urban teenager fascinated by traditional rhythms. Possessed by an overwhelming desire to understand this universe, at the age of nine, she started to visit the Casa da Cultura do Alto Maé.

“My father took me to meet with my drums,” says the choreographer of the show “Lady Lady” to Mia, who listens to her attentively.

He crossed the city limits to learn traditional dances, believing that in the suburbs he would find them genuine, free from modern and Western contamination.

Edna Jaime is writing her story on this journey that she has been travelling for over 20 years, getting involved with different forms of dance. The narrative of her life takes shape from the experience of crossing the traditional and the contemporary with the vocalist and dancer Lucas Macuácua, founding member of the Timbila Muzimba orchestra.

The definitive encounter with contemporary dance was in 2001, in a workshop directed by the Brazilian Lia Rodrigues, held by CulturArte.

“I wasn’t interested, but Lucas insisted and I was obliged,” remembers Edna, with a laugh on her lips. “I was wrong, I’m glad I was wrong,” she continues, to reveal an initial hesitation in relation to contemporary dance.

“Unlike a scientific career, which requires certainty,” Mia reacts, “in art you have to walk from discomfort to discomfort, that is to say, the moment you feel comfortable, art dies.”

When Mia started, in the 1980s, publishers defined which African authors should write about magical universes, conversations around the campfire and other stereotypes. But reality proved to be plural and diverse. This trip, he jokes, is equivalent to Edna’s trip to the outskirts of Maputo.

The choreographer says that, in this pandemic period, she is developing with the audiovisual artist Ivan Barros a work that reflects on the uses that are given to capulana as a way of preserving it. She wants to throw a stone into the pond of the meanings that Mozambicans give to this fabric of Persian origin.

“I was wondering,” she said, “after seeing the dress of the costume whose pattern is used by healers, how will people interpret it. Am I mixing subjects of traditional medicine and women? But I took the risk to bring it to reflect on a pattern that we didn’t create.”

Admittedly an uncoordinated dancer – rhythm, only in poetry – Mia found, as he revealed and Edna agree, his dance with words to be very successful.

The invention of words in Portuguese, the writer explained, has the purpose of meaning the language as it is spoken and perceived by Mozambicans. “[I want to] bring (Mozambican) orality into writing.”

The country he found as a journalist revealed to the writer that the grammatical language did not obey the choreography of ordinary speech, it does not go in the same direction as the articulation of everyday people. That is why I found in neologisms a way to portray the performance of our experiences.

Responding to Edna about his source of simplicity, Mia said that it was by watching his father and that it was with him that he also realized that art is the availability to be the other.

Perhaps it is this context that makes him “not care” about the great literary prizes. Beyond Camões, Albert Bernard or Neustadt, his greatest award was spontaneously awarded to him in one of the streets of Beira.

“Passing the ruin of the Grande Hotel, in the city of Beira, when I was writing my last book,” the write revealedr, “in a park over there was a man perhaps over 90 years old, surrounded by his grandchildren, great-grandchildren and he made a gesture to me, I approached him and he asked to hug me and said: I want to thank you for being a little bit of all of us.”

Issue 67 May/Jun | Download.

0 Comments