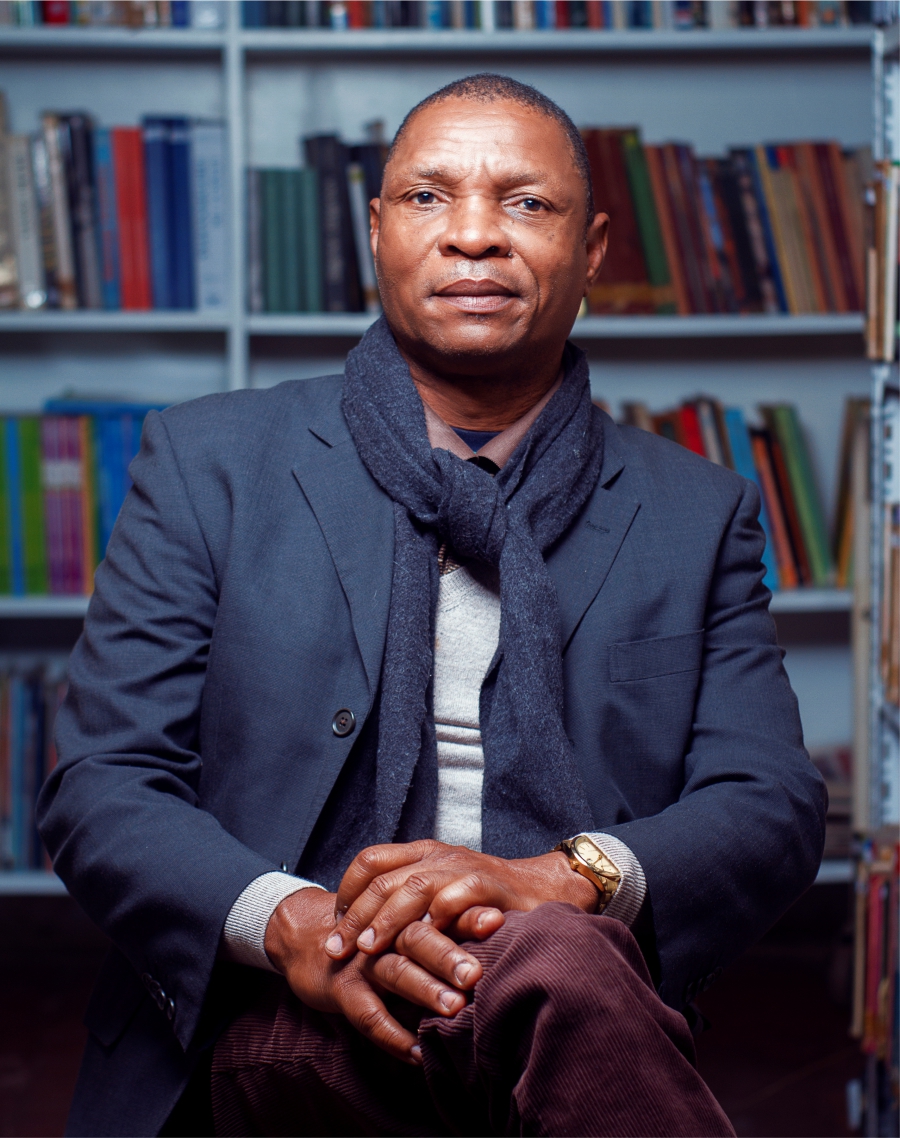

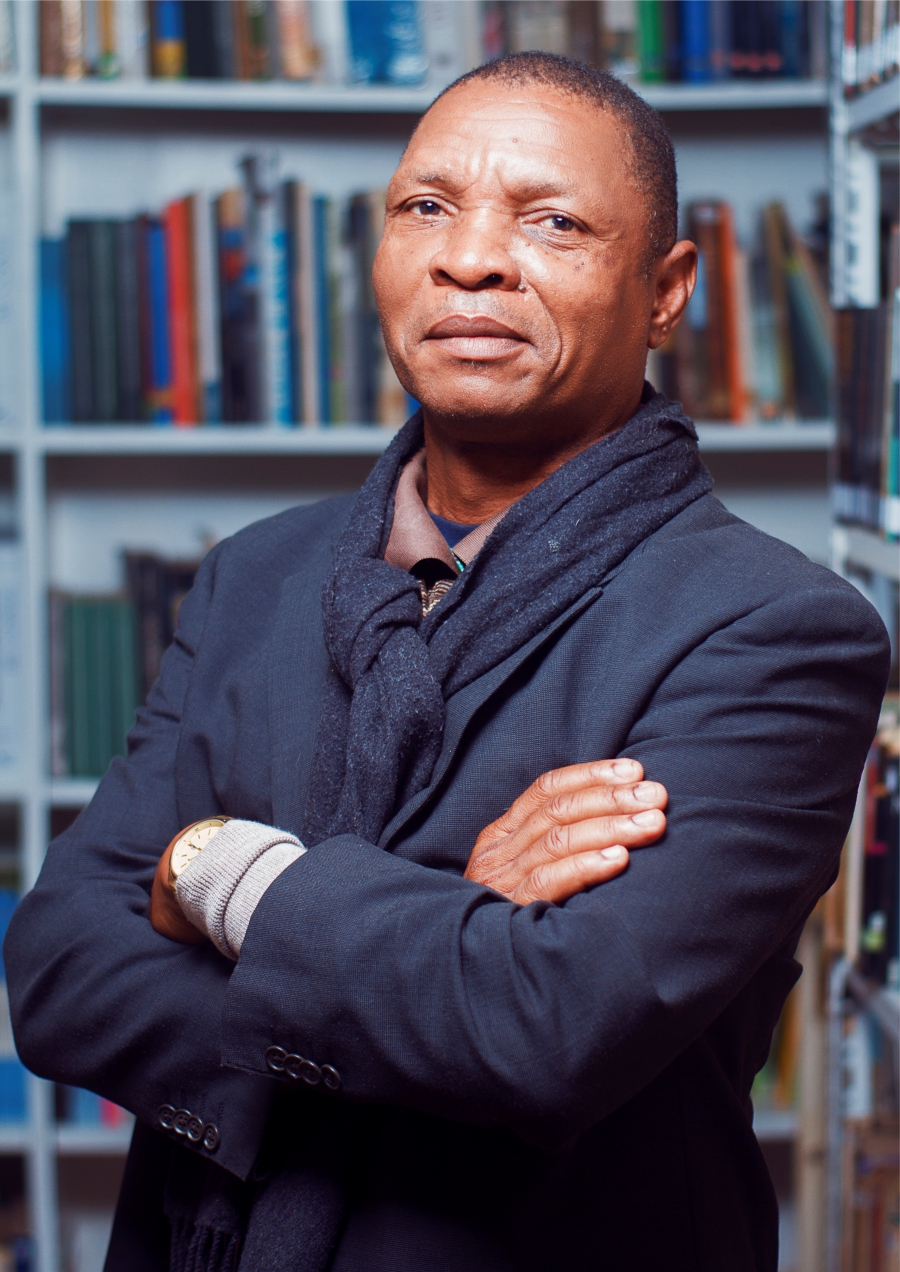

Suleiman Cassamo – An obsession for words

“It came from the burning sunset, from the end of the world, by the back shortcut. It was in the last song of the quails, in the last flight of the turtledove, the prayer of the frogs in the swamps, the earth covering itself with shadows and silence. The dead, when they return, they said, bring the heavy cross from their own tomb, bending their spine. However, no one has ever seen them return.”

Advertising

A rough and vigorous shortcut of synthesis, made up of silence. It’s along this path that Suleiman Cassamo advances, in his debut book, “O Regresso do Morto” (AEMO, 1987). Each word has due merit, calculated, balanced so that a kind of abstract equality is established, between what is told and how it is told and still move the reader. It’s not just in this book. The author’s entire literary path seems to establish a connection between the written text and orality, the land and the people, speech and gesture, astonishment and enjoyment, giving the whole an atmosphere filled with humanity.

My work is laborious (…), there is this look, word for word, there is a judicious choice, as if that single word, that exact word, deserved a place in the sentence

Anyone who knows Suleiman Cassamo knows that the moment he leaves his house, the moment of farewell, is full of hesitations, a kind of silent prayer. It is not by chance that Suleiman was born in the midst of Ronga culture (on his mother’s side) – where the gesture of saying goodbye is ceremonious – and Islamic (on his father’s side). As a child, he learned traditional games: ntchuva, zotho, ntumbeleluana, mudjobo. It was only later that came the magazines, books and his literary fathers: Edgar Allan Poe, Ernest Hemingway, William Saroyan and Juan Rulfo, the latter, perhaps, being his greatest master.

For Suleiman, more than stories and words, literature is made through images, “words are worth nothing by themselves. The words can be simple, but the images must be strong”, he said.

In 2022, he should have published a book of short stories. As that was not possible, he started rewriting the last book he published. For those who’ve read it, one can tell the difference between the Angolan edition “A Carta da Mbonga” (2016) and the Mozambican edition “A Carta da Mbonga – Fragmentos Duma Vida Encalhada na Estação” (2021), immediately on the first page.

“I believe that, for some authors, the text is done in a single step. My work is laborious, slow, precisely because there is this care, this look, word for word, there is a judicious choice, as if that single word, that exact word, deserved a place in the sentence.”

Following a path almost parallel to that of his master Juan Rulfo, Cassamo made his debut as a writer 34 years ago, and has published four books. Rulfo published three books, but assumed the authorship of only two: “The Plain in Flames”, a collection of short stories from 1953 and “Pedro Páramo”, a novel from 1955. Suleiman’s divides his life is split between his work as a writer and as a university professor, in Materials Science and Engineering and Economics. In addition to “O Regresso do Morto” and “A Carta da Mbonga” (União de Escritores Angolanos, Luanda), he also published “Amor de Baobá” (Mozambique and Editorial Caminho in Portugal, 1997), an almost non-existent book; “Palestra para um Morto” (Mozambique and Caminho in Portugal, 1998), an exceptional and intelligent work, perhaps the least understood.

Polishing words until their concrete and necessary shine emerges requires more than talent and work, it requires patience and the ability to improve common codes so that they become notable literary objects. This is possibly the main skill of the author of “Ngilina, tu vai morrer”.

▶ Highlights

The entire literary path of Suleiman Cassamo seems to establish a connection between the written text and orality, the land and the people.

“My work is laborious (…), there is this look, word for word, there is a judicious choice, as if that single word, that exact word, deserved a place in the sentence.”

Edição 77 Jan/Fev| Download.

0 Comments