Ungulani Ba KaKhossa – A train loaded with rubble from the past

We don’t choose our literary path. It’s what takes us to the hostels – a term almost in disuse – of this life marked by imponderable acts and scenes.

We read the last page of “OsSobreviventes da Noite‘’ (The Night Survivors)(Cavalo do Mar, 2021)and think of Penete’s clipped voice insisting on returning to pick up his cage, after leaving the great night that is every day in every war. The cage is material and metaphorical, the box of wire trapping him in the past. And Severino’s voice, the most experienced of the group of child soldiers, points to the future like the child’s hand on his father’s shoulder at the statue of Pierre Goudiaby on Dakar’s twin hill.

Adversiting

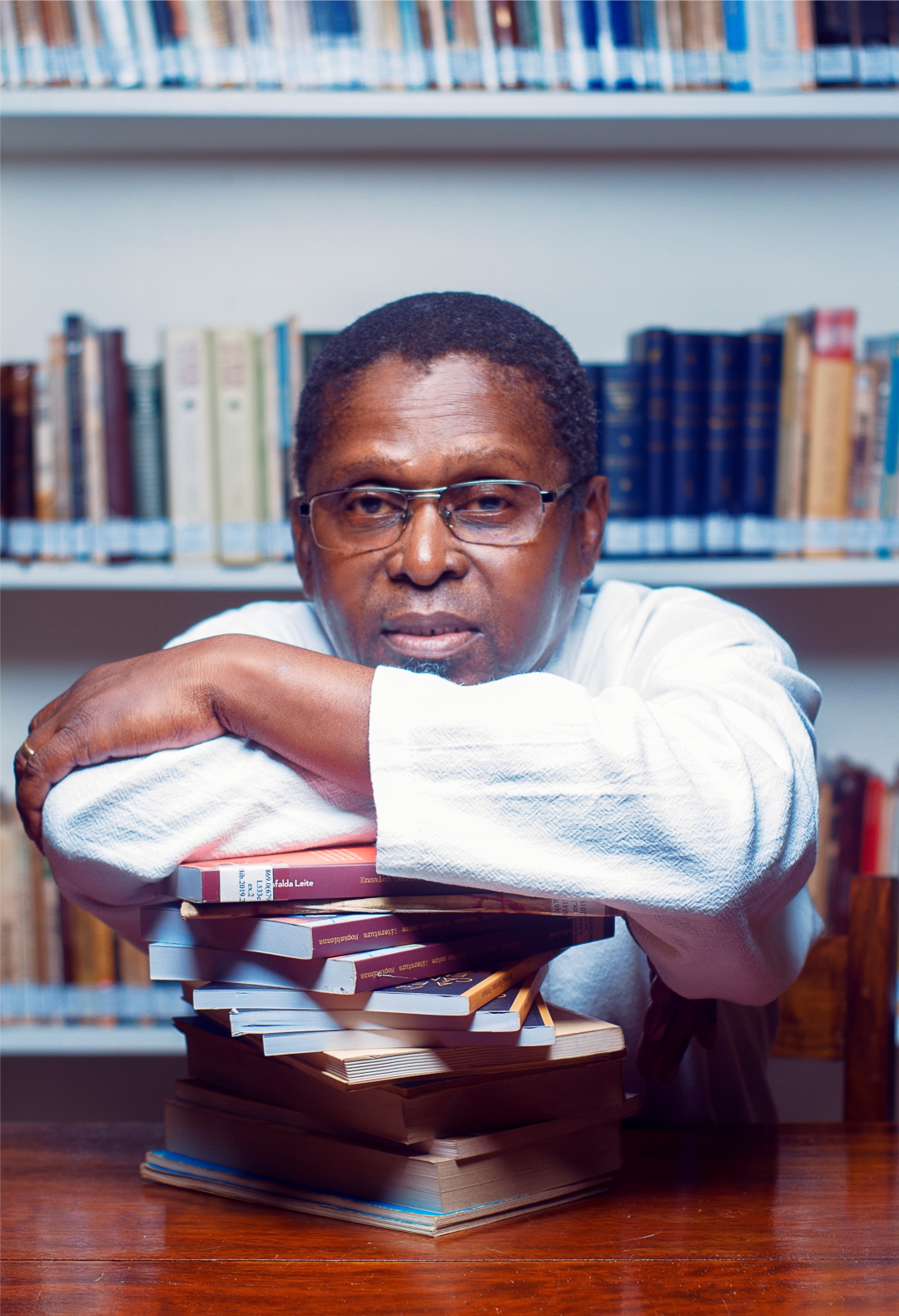

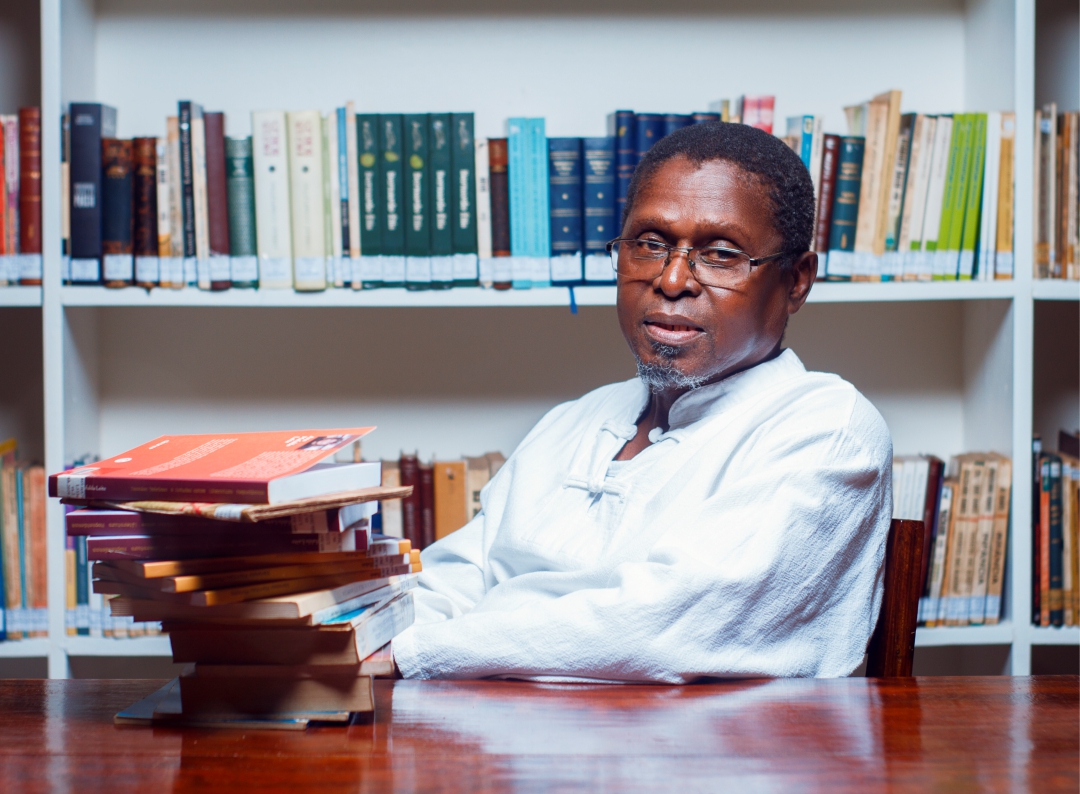

In that last dialogue, in that exchange of sentences hinting at the oasis after the desert of blood, we have the greatest image of Ungulani Ba KaKhosa’s Literature (b. 1957), a train loaded with rubble from the past whistling when it sees us crossing the line. As he said in an interview with fellow writer Marcelo Panguana, in the book that is a celebration of friendship ‘’OsPeregrinos da Palavra‘’ (The Pilgrims of the Word) (Alcance, 2018), history, whether capitalised or minuscule, only interests him as a pretext for the present. ‘We don’t choose our literary path. It’s what takes us to the hostels – a term almost in disuse – of this life marked by imponderable acts and scenes,’ he told us in an interview that took him a long time to give.

Ungulaniscrutinises the minutiae of the past in order to talk about today, in order not to allow the past to repeat itself, in order to open the curtain of the present with two fingers, in order to let us see the future, which may be bleak, even if it’s a sliver. That’s why the train whistles. The last speech by Ngungunhane in ‘Ualalapi’ (Alcance, 1987), the book that paved the way for him, was proof of this. Ngungunhane’s last speech, which came out of the present in which the book was published, is still very relevant to our time. More than 30 years later, we realise that much of what we find again in this “Assimnão, Senhor President” (Not so, Mr President), strangely shrouded in a fog of silence, was already announced. While it’s true that in our circles books aren’t the product of much attention, it’s no less true that there are books chosen to be celebrated, and they’re always the ones that move in the grey landscape of lullaby themes.

‘Not so, Mr President’ is provocative, right from the title, a stone in the jar of a period that is spoken of with a tongue tied, only in mumbles. It is perhaps the most political book Ungulani has written. And perhaps we can understand why he has only come to this book now, after eight books have been released, all the national literary prizes have been won, and he is sitting at the table of the big five with his grey hair already claiming his time in his always well-groomed goatee. This ‘Not so Mr President’ deals with the iniquities of the Samora regime and could only have been written by a writer who has reached maturity, resting in his Marracuene next to his life partner who is also his work partner and signs the revision of this book – Salomé Pinto Sousa, far from the co-opted sectors.

António Furtado, the book’s main character, is a linguistics professor who is what most intellectuals seem to have given up on being – a voice questioning the directives that very much define the way we perceive life today, the cult of personality that accommodates and perpetuates the same elites always ready to castrate the dissonant voice of the symphony in C-minor.

In the long-winded paragraphs, like the 800 metres swimmers, we find a tone that borders on the confessional and we think of António as Ungulani’s alter ego, just as Nathan Zuckerman was Philipe Roth’s alter ego. Without assuming it, Ungulani speaks of a farewell to an entire generation that doesn’t seem to have the muscle to make the move to the new times in which we live. Thetrainhaswhistled.

Edição 85 NOV/DEZ| Download.

0 Comments